Special Collections has a number of interesting books on Native Americans and the westward expansion of the United States, with particular focus on relations between Native Americans and Europeans moving into the American West. These books often include descriptions of tribal life,  customs, and language as encountered and recorded by Europeans. One example is Caleb Atwater’s Indians of the Northwest (1831). Atwater was an archaeologist known for work on the mounds and earthworks of the Ohio Valley. In 1831 he published his experiences while he was employed by the United States government to negotiate with the people of the upper Mississippi. In the book he described customs, including games, music, and dancing. Atwater also recorded lists of common words in the Sioux or Dacota language.

customs, and language as encountered and recorded by Europeans. One example is Caleb Atwater’s Indians of the Northwest (1831). Atwater was an archaeologist known for work on the mounds and earthworks of the Ohio Valley. In 1831 he published his experiences while he was employed by the United States government to negotiate with the people of the upper Mississippi. In the book he described customs, including games, music, and dancing. Atwater also recorded lists of common words in the Sioux or Dacota language.

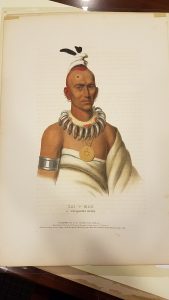

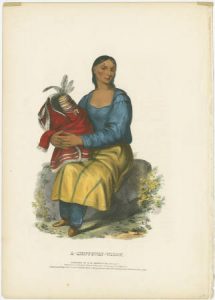

Examples from another interesting and important work can be found in the Library’s Hilde P. Holme Print Collection (find scanned images in Digital Maryland). The collection includes a small group of hand colored lithographs originally part of a larger work, McKenney and Hall’s History of the Indian Tribes of North America (1836-1844). The prints are thought to be some of the most accurate 19th century portraits of Native Americans. Many of the prints are based on the portraits of Charles Bird King who was hired by McKenney, then Superintendent of Indian Affairs in the U.S. War Department, to preserve the likenesses of treaty delegates visiting Washington, D.C. for negotiations. McKenney was rightly concerned about the tribe’s culture under threat of settlers and unsympathetic government officials. Then President Andrew Jackson was critical of McKenney’s sympathies toward Native Americans and in 1830 removed McKenney from office. McKenney then secretly had the original portraits copied for engraving so that the lithographs could be made. They were eventually published in a three volume set that included brief descriptions that accompanied each lithograph. King’s original portraits were moved to the Smithsonian, but most were destroyed by fire in 1865. All that is left are the hand colored lithographs.

Examples from another interesting and important work can be found in the Library’s Hilde P. Holme Print Collection (find scanned images in Digital Maryland). The collection includes a small group of hand colored lithographs originally part of a larger work, McKenney and Hall’s History of the Indian Tribes of North America (1836-1844). The prints are thought to be some of the most accurate 19th century portraits of Native Americans. Many of the prints are based on the portraits of Charles Bird King who was hired by McKenney, then Superintendent of Indian Affairs in the U.S. War Department, to preserve the likenesses of treaty delegates visiting Washington, D.C. for negotiations. McKenney was rightly concerned about the tribe’s culture under threat of settlers and unsympathetic government officials. Then President Andrew Jackson was critical of McKenney’s sympathies toward Native Americans and in 1830 removed McKenney from office. McKenney then secretly had the original portraits copied for engraving so that the lithographs could be made. They were eventually published in a three volume set that included brief descriptions that accompanied each lithograph. King’s original portraits were moved to the Smithsonian, but most were destroyed by fire in 1865. All that is left are the hand colored lithographs.

Explore more history in Digital Maryland.