by Tom Warner, Best & Next Department

Baltimore native & 1st African American Actor to appear in a starring film role

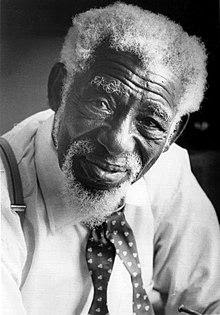

Clarence Muse was the first African American actor to appear in a starring role in film (1929’s Hearts in Dixie, an early “talkie” that was also the first film to feature an all-Black cast) and the first African American Broadway director (1943’s Run, Little Chillun). Born in Baltimore on October 14, 1889, Muse acted for over 50 years and appeared in more than 150 films. He was also a screenwriter, director, singer, composer, and author, and helped pioneer the Black Theater movement as an acclaimed performer with two Harlem Renaissance troupes: the Lincoln Theater Players and the Lafayette Theater Players. He was a co-founder of the all-Black Lafayette Players, who gained national acclaim with stagings of Orson Welles’ Voodoo Macbeth (1936) and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Of the latter production, Muse famously said the play was relevant to Black audiences because, “It was every Black man’s story. Black men too have been split creatures inhabiting one body.”

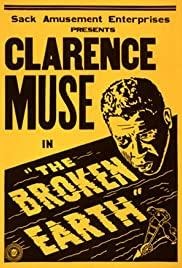

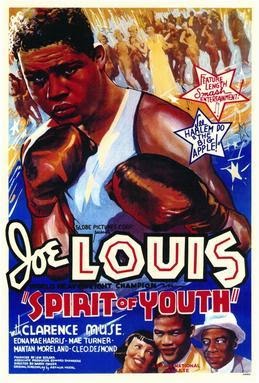

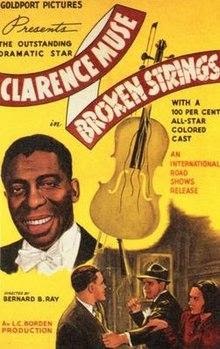

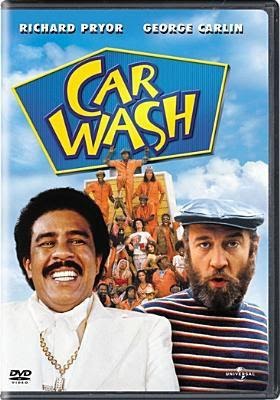

Among Muse’s many accomplishments in the arts, he co-wrote the screenplay for Way Down South (1939) with Langston Hughes and in 1931 co-wrote “When It’s Sleepy Time Way Down South,” which later became a signature song of Louis Armstrong. Highlights of his film career include star turns in The Broken Earth (1936) and Broken Strings (1940), co-starring with Joe Louis in Spirit of Youth (1938), and playing Peter the Honey Man in Otto Preminger’s Porgy and Bess (1959). After being considered for the role that went to Dooley Wilson in the 1942 film, Muse appeared as “Play It Again” Sam the pianist in the 1955-1956 TV version of Casablanca. Other notable film credits include the Disney TV miniseries The Swamp Fox (1959), Buck and the Preacher (1972), Car Wash (1976), Larry Clark’s Passing Through (1977) and Carroll Ballard’s The Black Stallion (1979).

Dvd

Muse was inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame in 1973 and in 1978 received a doctorate from Penn State’s Dickinson School of Law, where he studied Law briefly in 1908 before leaving to pursue an acting career. He continued acting up until age 89, last appearing as fruit and vegetable seller “Snoe” in 1979’s The Black Stallion. He lived until October 13, 1979 – one day shy of what would be his 90th birthday and four days before the release of The Black Stallion.

Despite a celebrated career, many of Muse’s early films remain hard to find. Thankfully, Pratt has a number of Clarence Muse films, including a rare interview taped just months before his death, available to check out using our Sidewalk Service or Books-by-Mail resources:

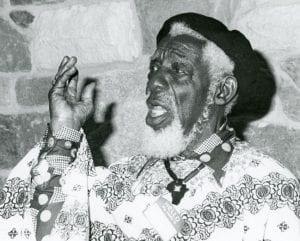

Host Dr. Winona Fletcher (Indiana University) interviews Black actor and vaudevillian Clarence Muse a few months before his death in 1979. Muse reminiscences about his professional life, particularly the formation of the Lafayette Theatre Players.