by Julie Saylor, Maryland Department

Photograph by Eli Pousson

Due to the pandemic, you can’t visit us in person in the Maryland Department at the moment. But there’s another place to get your history fix while getting a bit of fresh air and exercise—your local cemetery. Far from being morbid reminders of death, cemeteries are beautiful places, full of art, history, and nature. If you visit, you’ll be using them as they were used in the past, because cemeteries were our first parks.

The first resting places for the dead in America were “burial grounds,” located on the grounds of churches and meeting houses. Gravestones were carved with skulls and other symbols reminding the visitor of their inevitable death. Attitudes toward death began changing in the nineteenth century, which had an impact on cemetery design.

As cities grew, burying grounds became too crowded to accept more interments, and the public health implications of overcrowding meant that cities had to find other places for their dead. Thus the “rural cemetery” movement was born. Rural cemeteries were located on the outer edges of cities. Their pastoral landscapes encouraged the living to enjoy the quiet and picturesque beauty of nature, while paying respect to the dead. The first rural cemetery in the United States was Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery, built in 1831. Others soon followed: Laurel Hill Cemetery, built in Philadelphia in 1836, and Green-Wood Cemetery, built in Brooklyn, New York, in 1838.

These were not burying grounds connected with any particular church; they were nonsectarian, open to any family who could afford to purchase a plot. Both the wealthy and the middle class found these new cemeteries a gratifying respite from the congestion and noise of the city. Rural cemeteries became a sought after tourist destination. Some cemeteries allowed carriage rides and picnics, and all allowed strolling and space for rest and contemplation.

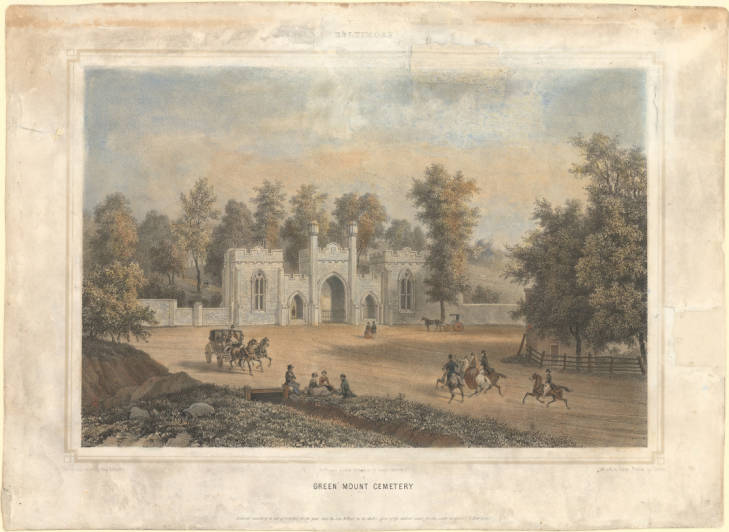

Baltimore tobacco merchant Samuel D. Walker began a campaign to build a rural, nonsectarian cemetery after visiting Mount Auburn in 1834. The site selected was at the city’s northern edge, an estate called Green Mount, once the home of the merchant John Oliver. The layout of the cemetery was designed by Walker and architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Jr. They built winding paths and incorporated an elm-lined lane, “Oliver’s Walk,” a remnant of the original estate. The magnificent stone entrance gate was designed by architect Robert Cary Long, Jr.

Green Mount Cemetery was dedicated the evening of July 13, 1839, “in the open air, in a grove of forest trees.” Congressman John Pendleton Kennedy urged the visitor to experience “[t]he sanctity and the silence of the place, with its quiet walks, its retired seats beneath overhanging boughs, its brief histories chronicled in stone, and its moral lessons uttered by speaking marble,–all these should allure him to meditate upon that great mystery of the grave…”

Not all came to Green Mount for meditations on mortality. In 1848, a visitor from New York wrote to the Baltimore Sun. He recommended the cemetery as a must-see tourist spot: “[n]o one should fail to visit Green Mount Cemetery. It almost bears comparison to our Greenwood” (September 5, 1848, p. 1). A writer to the Sun in 1842 complained that some visitors picked “flowers which are kept as sacred property” (November 2, 1842, p. 2). The cemetery board tried to quell the throng of visitors by restricting admission to lot holders and their families. Strangers could only enter with a ticket obtained at the gatehouse, and never on Sundays. “A friend to the Ladies” wrote to the Sun that this requirement was too restrictive, warning, “[i]f that edict is not reversed, I think some persons will have the ladies about their ears thick as bees…” (May 27, 1841, p. 2).

After the establishment of parks, cemeteries were largely forgotten as a place for recreation. But Baltimore’s cemeteries are still there for anyone wanting a quiet place to walk, watch birds, or appreciate history and beautifully carved monuments. Rural cemeteries offer a special appeal in this time of pandemic. These “cities of the dead” are home to Baltimore’s quietest residents, who will respectfully maintain their social distance, six feet underground.

Are you searching for a cemetery near you or want to find a grave of your ancestor or a famous person? A good place to start is Find A Grave: www.findagrave.com.

With your library card, you can search for articles about cemeteries or your ancestors by using our many online, searchable newspaper indexes, including the Baltimore Sun, the Baltimore Afro-American, and Newspapers.com: https://www.prattlibrary.org/research/database/?sbj=152.

Digital Maryland is a great place to search for historic images of cemeteries and for African American funeral programs: https://www.digitalmaryland.org/.

If you need help navigating our online resources, need help with genealogy, or have questions about Baltimore’s history, you can always email us in the Maryland Department at mdx@prattlibrary.org. And, of course, make sure to visit us at the Pratt Library once we are again open to the public!