Beat the heat with a refreshing treat this July! Check out these cookbooks spotlighting frozen sweets.

From the pure, radiant flavors of classic Blackberry and Spicy Pineapple to unexpectedly enchanting combinations such as Sour Cream, Cherry, and Tequila, or Strawberry-Horchata, Paletas is an engaging and delicious guide to Mexico’s traditional–and some not-so-traditional–frozen treats.

Paletas, by Fanny Gerson and Ed Anderson, eBook

With little skill, surprisingly few ingredients, and even the most unsophisticated of ice-cream makers, you can make the scrumptious ice creams that have made Ben & Jerry’s an American legend.

Ben & Jerry’s Homemade Ice Cream & Dessert Book, by Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield, eBook

Popsicles are the perfect treat for a warm day or just when you want a sweet cool treat. They are easy to make and can be packed with lots of flavor. Store bought popsicles are good, but nothing beats a homemade popsicle made of your favorite fruits and flavor combos.

Popping Popsicle Recipes, by Gordon Rock, eBook

Recreate the classic and nostalgic flavors of your youth with ice cream recipes for French vanilla, chocolate, strawberry, coffee, rocky road, and so much more!

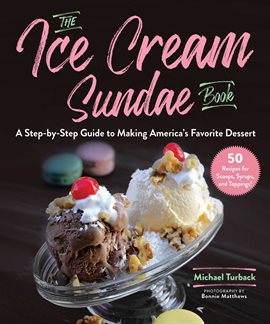

The Ice Cream Sundae Book, by Michael Turback, eBook