by Lisa Greenhouse, Librarian

by Tom Horton

Book

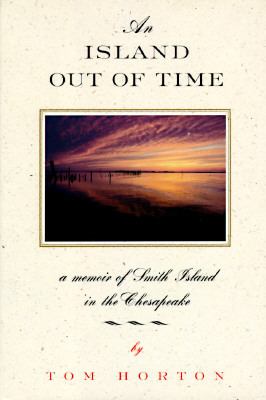

In 1987, science writer Tom Horton quit his job with the Baltimore Sun and moved with his wife and children to Tylerton, one of three small towns on Smith Island in the Chesapeake, Maryland’s only inhabited Bay island. Horton spent two years in Tylerton, working as an environmental educator with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. Horton’s book, An Island Out of Time: A Memoir of Smith Island in the Chesapeake (W.W. Norton & Co., 1996), is part memoir, part oral history, part ethnography, and part elegy.

Author

The book’s title is doubly suggestive. It captures the sense that Smith Island is an island out of time, a time capsule where some 17th Century folkways and speech patterns persist. Yet the book’s title also conveys a sense of impending loss. With multiple environmental pressures bearing down on them — overfishing, climate change, pollution — Smith Islanders don’t have much time left. They are almost out of time. In 1994, the population of Tylerton was 90, a 41% decline from 1980. Currently around 50 people live in Tylerton. During Horton’s stay, the young people were leaving, going to college or taking jobs at the mainland prison, opting out of the waterman’s trade that had been handed down for centuries.

Horton sends tapes of Smith Island speech to a British linguist and determines that the speech patterns of the Islanders are very similar to those of nineteenth century Devon in southwestern England. Some have claimed that the Island speech patterns are Elizabethan, but the linguist tells Horton that it is not really known how ordinary people spoke in Elizabethan times. The nineteenth century Devon speech patterns were, however, at least three centuries old.

However far back the speech patterns and folkways of Smith Islanders can be traced, Horton paints a picture of an eccentric people. Most Smith Islanders are highly religious, steeped in a traditional form of Methodism, which has much more in common with contemporary evangelicalism than with today’s Methodist Church. At the same time, the conversation of Smith Islanders, both men and women, is peppered with bawdy sexual references, enough to make even a cosmopolitan mainlander blush (once their meaning is understood, that is). One Smith Islander, for example, refers to her daughter as Boss Tippet (see page 106 for a translation).

Horton paints Smith Islanders as what he terms “Christian outlaws.” They have lived off the bounty of the Island for so long that encounters with various environmental police forces have not always been amicable. Who are the Game and Wildlife Police to tell them they can’t shoot or trap the waterfowl that they have been harvesting for centuries?

Islanders still talk about an incident in which a young Smith Islander was shot and killed by a Virginia fisheries patrolman as if it occurred yesterday. Horton is surprised when he finds out the shooting occurred around 1900. In a part of Maryland where the sea and the land blend indistinctly, borders are not an easy concept to grasp, and the border between the grassy, shallow waters of Maryland and Virginia, abundant with blue crabs, was once fraught with conflict.

The state regulatory apparatus impinged more and more on the traditional way of life of the Smith Islanders as the twentieth century wound down. While soft crabs were the main source of income on Smith Island, wives of the Island watermen had for many years supplemented their incomes by picking hard crabs in their homes. In the early 1990s, Maryland made it clear that it would no longer tolerate crab picking as a cottage industry and that if the picking was to continue, it would have to be in a modern facility with state of the art hygiene and food safety features.

Next, Somerset County, approached the Islanders about installing a modern water treatment plant. All of this regulation seemed unnecessary to the Islanders who had been drinking water directly from the well and picking crabmeat at home for many a year seemingly without problems. The environmental regulation seemed unfair as well. The Islanders saw themselves as a critical part of the Chesapeake ecology. Their harvesting of nature’s bounty, whether it be hunting for waterfowl, fishing, crab scraping, or oyster dredging, seemed to them essential to the health of the ecosystem. They couldn’t quite explain exactly how this was true. Yet they seemed to accept it as an article of faith as true as the ones brought to the Island by Joshua Thomas, the Methodist preacher who converted the Chesapeake Bay islands in the early nineteenth century.

The Maryland Department has many books about Smith Island. From Amazing Grace: Smith Island and the Chesapeake Watermen by Bernard Wolf (Macmillan, 1986) to Workboats of Smith Island by Paula J. Johnson (JHU Press, 1987), the Maryland Department’s Collection is a great way to learn about Smith Island before you take the ferry over.